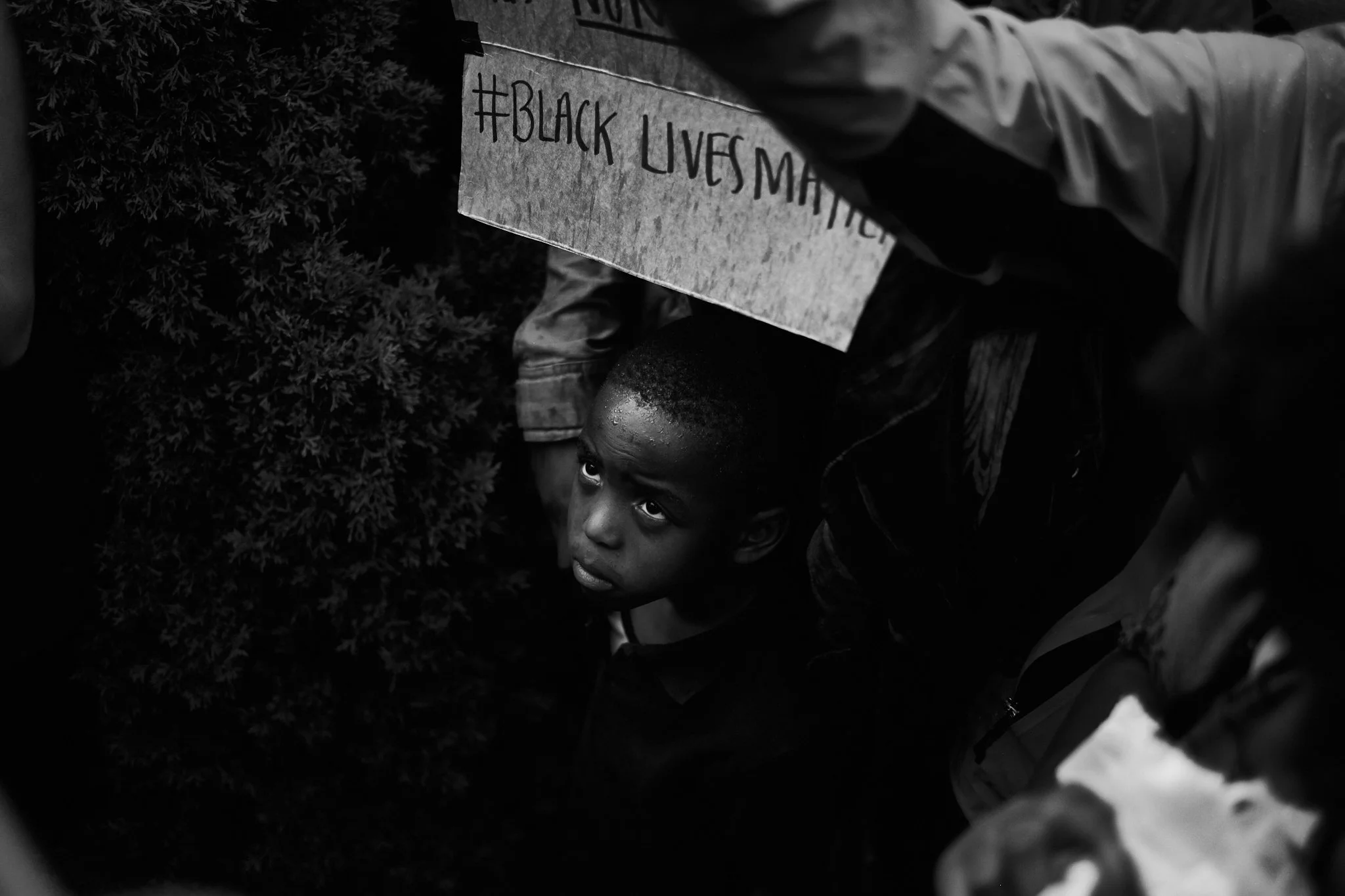

Can You See Me?

By DeJuan Mason

He promised to take me with him to the next protest. He said that I needed to learn how to stand up for my community, stand with my brothers and sisters and rage against the machine. I never knew what he was talking about, but he was my big brother, and I loved hearing him talk.

Jabari was 9 years old when I was born, and my mommy said it seemed like he wanted me more than her and my daddy. I didn’t know it, but he was known in the neighborhood as the next Michael Evans; young, full of righteous indignation and vigor. The ladies in the laundry room always smiled when his name came up in conversation. The girls on the playground smiled behind their hands and giggled when his name was mentioned, especially Jaleesa Vincent. I think Jaleesa was Jabari’s girlfriend or wanted to be. She was tall, with long arms and legs and played volleyball for the high school. I think Jabari thought she was pretty, but he always said he didn’t have time for a girlfriend because his community was dying. I never understood why he said it was dying — I used to see Lucky Sam outside the five and dime every day on my way to school. Lucky Sam lived on the park bench by the school. Folks called him Lucky because he was able to fall asleep standing up and never fell over. Sometimes he would wander in the middle of the street in a daze and never get hit by a car. Jabari used to give his lunch to Sam, but all Sam would do was take the bread off the sandwich and feed it to the birds. Across the corner from Sam’s bench was the playground. It had a swing, a sliding board that got too hot in the summer, a seesaw that Mommy wouldn’t let me play on because the wood scraped my leg one day, and monkey bars.

When I was a little boy, Jabari used to push me on the swings. He would tell me that all I could touch was mine because I was the descendant of African kings. (BREAK) I didn’t think that was true because my daddy was from Cleveland and my mommy was from Memphis and I was pretty sure neither of those cities were close to Africa. But when I was swinging, Jabari made me feel like I could touch the sky, and I loved the idea of thinking I was touching the hand of God.

Matter of fact, the only thing that died in our community was Jabari. It was the summer before my 10th birthday, and I had just become a Boy Scout. I was so excited! My daddy signed my permission slip, telling me about all the fun he used to have when he was a scout. He said his time as a Boy Scout and then an Eagle Scout was what led him to join the Marines. He loved being a part of something that was a brotherhood without being a bougie fraternity. Daddy disliked everything about college life except my mother.

They met when he was stationed at the Marine barracks, and she was a junior at Trinity University. Mommy said she had stopped to meet some friends from Howard at Blimpies sandwich shop for lunch. They got their food and left the restaurant, crossing Georgia Avenue against traffic to get to campus. Mommy heard the screech of tires before she saw the car that almost hit her. The driver’s door opened and out stepped the most beautiful set of teeth she had ever seen. Lucky for her, those teeth were surrounded by strong lips that were perfectly framed by a mustache and goatee. What she didn’t hear was the owner of those teeth berating her for not paying attention to traffic. Once daddy stopped yelling at her, he took a good look into what he said were the most clear amber eyes he had ever seen. He began apologizing for his tone, offered her a ride anywhere she wanted to go, and they spent every day together after that moment.

Jabari didn’t like the idea of the Boy Scouts, or the Marines or the police. But he loved the idea of me. While we were walking back from the store, we saw a man beating his girlfriend. Jabari told me to run home. I tried to tell him that we should call our father, that it wasn’t any of our business, but he couldn’t hear me. He was running across the street toward the couple. I guess he didn’t hear the police officer yelling at him, either. I heard Jabari say, “Hey man, leave her alone!” Then I heard the police officer say, “Stop!” Someone screamed, tires screeched, I turned toward the sound and saw Jabari’s body fly in the air. When he landed on the sidewalk, his face contorted somewhere between grinning and shock. The sound of his head hitting the concrete reminded me of the sound the garbage man made when he threw our trash cans back in our yard; loud and hollow.

I dropped my bags and started running towards him when large hands grabbed me, stopping me mid-run. Someone had told my parents there was an accident and my father had come running down the street just in time to see me about to dart out in the same street where Jabari had been hit.

That was last summer. Jabari’s body lies in a cold grave; his room looks like it’s waiting for him to come home from school. The police officer who hit him got transferred to another district when the community started demanding he get fired.

There have been protests every day since my brother died. I don’t even know the people who are protesting; they’re not from our neighborhood. I’m out here today because it’s Jabari’s birthday. I picked up the last sign he ever painted. I wonder if the words are true.